Published by malaymail, image by malaymail.

It’s no secret that Malaysia grapples with gender disparities, ranking 102nd out of 146 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (GGGR) 2023, outperforming only Myanmar within the ASEAN region. Among the pivotal yet often under-discussed drivers of this disparity is the phenomenon of ‘career breaks,’ a challenge that predominantly affects women and hinders the path to gender equality for our nation.

A career break is a temporary absence from the workforce, typically lasting for six months or more. These breaks significantly shape an individual’s professional journey and disproportionately affect women who bear the brunt of caregiving responsibilities, particularly in a patriarchal society, leading to gender disparities in the Malaysian workforce.

Global research consistently indicates that women are more likely to take career breaks. For instance, the applied study in 2022 revealed that women are three times more likely to take career breaks for childcare (38%) than men (11%). On the other end, a 2020 study by LinkedIn and Censuswide found that 42% of women do so for caregiving reasons, compared to 28% of men.

At the heart of the gender disparity are the multifaceted challenges posed by career breaks, which demand our immediate attention. These challenges span a spectrum of issues, and their impact reverberates across the labour force, wage structures, and women’s overall economic independence.

Gender gap in the labour force participation

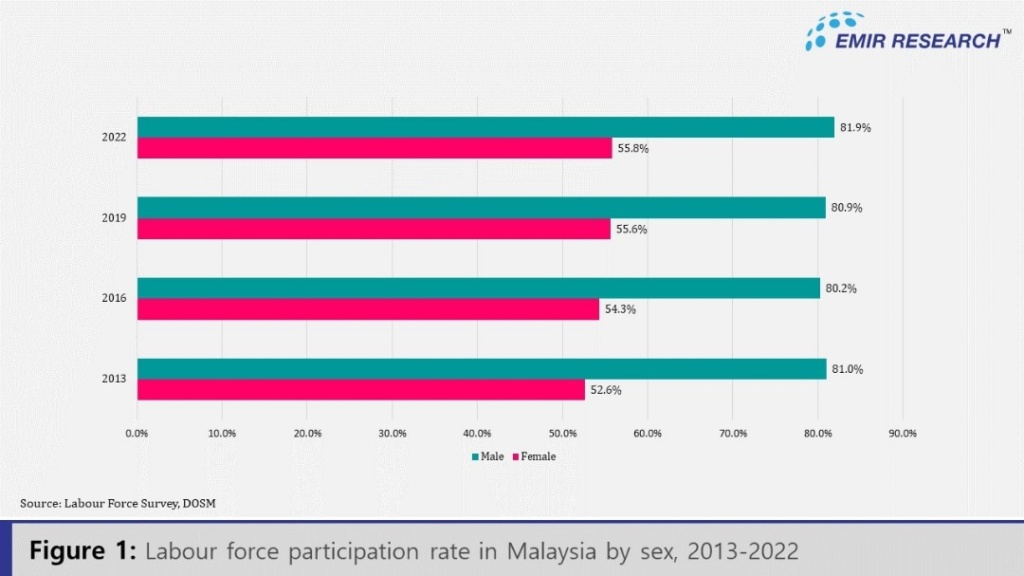

The labour force participation rate (LFPR) for males and females has been increasing consistently in Malaysia (Figure 1), suggesting a positive level of engagement.

However, the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) data indicates a persistent significant gender gap in LFPR. In 2013, there was a substantial 28.4% difference between males (81.0%) and females (52.6%), and by 2022, the improvement had been minimal, with a 26.1% difference.

Furthermore, it’s crucial to note that as of August 2023, the gap appears to start widening again — 26.7%, with 83.0% of males and 56.3% of females, as reported by DOSM. This fluctuation highlights the intricate nature of achieving gender parity in the workforce and suggests unresolved underlying issues.

In addition, comparing Malaysia’s female LFPR (FLFPR) with ASEAN peers like Singapore (63.2%), Thailand (58.4%), and Vietnam (69.1%), it has consistently ranked among the lowest, standing at a meagre 55.8% in 2022.

It’s perplexing that despite a higher percentage of women in Malaysia having tertiary education (47.3%) compared to men (35.8%), their labour force participation rate is significantly lower at 66.2%, in stark contrast to men (82.6%). The GGGR 2023 further revealed Malaysia’s female graduates (22.17%) outnumber male graduates (10.77%) by a significant margin of 11.4%. Meanwhile, in 2022, only 85.5% of women with at least a degree will be in the labour force, a notable contrast to the 94.5% of men.

These figures suggest either significant human capital waste or costly subsidy of foreign economies by Malaysia due to brain drain, highlighting the urgent need to boost the FLFPR, a critical tool in preventing brain drain, as recommended by the World Bank.

The enigma of the wage gap

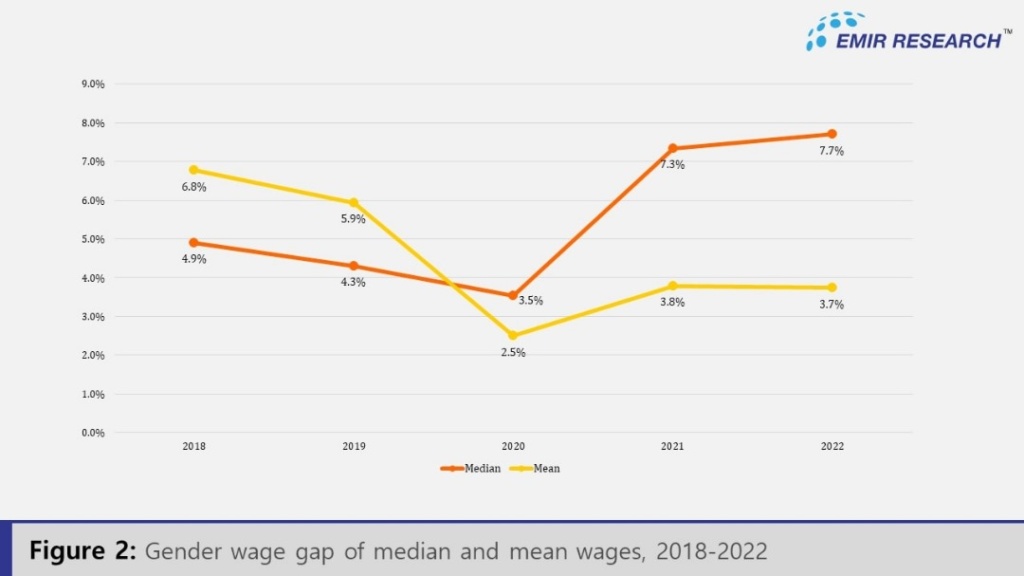

Another aspect of gender disparity is the wage gap (Figure 2).

In 2018, both gaps were 4.9% (median) and 6.8% (mean), improving to 3.5% and 2.5% in 2020. However, the subsequent increase in 2021, reaching 7.3% (median) and 3.8% (mean), indicates that the initial progress in narrowing the gap during those years was not sustained. By 2022, men earned 7.7% more than women in median wages and 3.7% more in mean wages.

In addition, Chief Statisticians Malaysia, Datuk Seri Dr Mohd Uzir, noted that men out-earn women because male workers often maintain longer continuous careers, while women experience more frequent career breaks due to family commitments and childcare responsibilities, which result in wage disparity.

This isn’t just about numbers; it exposes deep-seated labour market inequalities and underscores the urgent need for Malaysia to confront substantial gender equality challenges, particularly in addressing women’s underrepresentation in the labour force and the persistent gender wage gap.

The role of career breaks in gender disparities

Career break creates financial stress, particularly for women. They bear the sots of caregiving without the corresponding income, leading to financial insecurity and reinforcing the ‘motherhood penalty’. This penalty is intricately linked to the gender wage gap, resulting in women earning less when they return to work after a break. Career breaks, even as short as one year, are associated with significant wage losses, often around 4%, as “The Role of Firms in Wage Inequality: Policy Lessons from a Large-Scale Cross-Country Study” reported.

Furthermore, occupational segregation exacerbates gender disparity challenges associated with career breaks and is frequently cited as the primary contributor to gender disparities. It occurs when one demographic group, such as male or female, is overrepresented or underrepresented in a specific job sector and can even begin at the education level, where gender biases can steer students toward particular career paths.

For instance, boys may be pushed toward STEM while girls may be encouraged to pursue humanities or social sciences. This trend is reflected in the GGGR 2023, where data indicates 72.9% of engineering, manufacturing, and construction graduates in Malaysia are male, while only 27.1% are female. Therefore, when women take career breaks for caregiving reasons, re-entry challenges into these male-dominated fields become apparent.

Workplace biases, mainly where males are the majority of the workforce, are more prone to gender discrimination, affecting mothers who are at the greatest risk of employment gap stigma and entrenched norms significantly contributing to gender disparities. The 2022 PEW Research Center Survey highlighted that 61% of respondents believe employers treat women differently, emphasising workplace gender bias as a major reason for the gender gap.

Moreover, workplace policies in 4IR essential industries like manufacturing and engineering tend to favour male employees over female counterparts. Research by the Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) highlights the hiring disparities where male STEM graduates are preferred over female graduates (see “Malaysia’s gender gap in STEM education and employment”). Such gender biases limit women’s entry into industries where they are underrepresented, contributing to occupational segregation and limiting their access to career opportunities.

Returning mothers encounter challenges that can hinder their career progression, including being passed over for promotions, facing unfair treatment, or struggling to find opportunities commensurate with their skills and qualifications.

The fact that women have lower employment rates despite their higher education levels highlights the existence of discrimination in various forms. Particularly noteworthy, in the 2020 LinkedIn and Censuswide study, more than a third of women face hiring difficulties, and 61% struggle to join the workforce after a career break.

Consequently, despite often being undertaken for reasons like family obligations or personal development, career breaks can inadvertently contribute to the gender disparity.

As mentioned earlier, international experience attests that the gender divide is one significant force fuelling brain drain, thus compromising national progress.

Therefore, to bridge the gender gap in the workforce and boost Malaysia’s economic potential, we must fully engage women in the labour market, as highlighted by Nurul Izzah, co-head of the advisory committee to the finance minister.

Road to a gender parity workforce

Attaining gender parity is complex and requires all sectors to play their part in maximising work opportunities for women, in alignment with MADANI Economy: Empowering the People framework to achieve 60% FLFPR.

The government aims to provide financial aid, including subsidised daycare centers and entrepreneurial support programs, as part of the initiative. However, it is essential to complement these financial incentives with emotional and social support to empower women.

Thus, introducing group-based peer support tailored to individuals with career gaps in the form of mentoring programs or counselling services is a promising strategy with a proven track record in various countries, which at the same time can address the gender disparity. It has improved job retention and job placement and has significantly increased participants’ confidence, self-esteem, and social skills to help them build resiliency and bounce back from career setbacks.

Furthermore, relevant stakeholders must create a comprehensive framework outlining the program’s objectives, eligibility criteria, training for peer supporters, and a structured approach to delivering emotional and social support. Then, the government can maximize the positive impact of this initiative and provide women with a robust support system as they navigate their journey back into the workforce.

Notably, a cornerstone in the quest for gender parity and increase in FLFPR in Malaysia lies in tackling the prevalence of unconscious bias in the workplace. Eliminating these biases is crucial as it often leads to discrimination against individuals returning from career breaks, particularly women.

For instance, employers must implement gender-neutral processes in hiring, such as blind evaluation processes to recruit employees from diverse backgrounds based on their qualifications without being aware of their gender.

As we move forward, let’s support policies promoting workplace gender equality fostering inclusive growth, trust, resilience, and global competitiveness.

It’s a collective effort for a more inclusive and prosperous Malaysia that achieves the target of a 60% female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) within ten years. Only by achieving this goal can Malaysia genuinely bridge the gender disparities and work toward sustainable economic growth and development.

Farah Natasya is a Research Assistant at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.