[ad_1]

Published in Sinar Daily, Astro Awani, and Malaysiakini, image by Sinar Daily.

Brain drain is a serious problem in Malaysia. It is also a global phenomenon that has captured the interest of academic researchers and government since the 60s. However, this is not a trend that any country would like to see increasing in abnormally high numbers.

If we look at the very surface of the brain drain issue in Malaysia, some will attribute it to the poor execution of the affirmative policies that meant well but ended favouring selected few in nearly all spheres of socio-economic life. And they would not be wrong, although the poor execution of the affirmative policy itself is a symptom of a much more fundamental problem — the quality of the country’s stewardship.

Therefore, if we take these divisive policies as the first so-called ring-bell of a deeper structural problem of inferior country stewardship, we can historically trace it back to the tragic May 13 ethnic clashes in 1969 and the subsequent formulation of the affirmative policies.

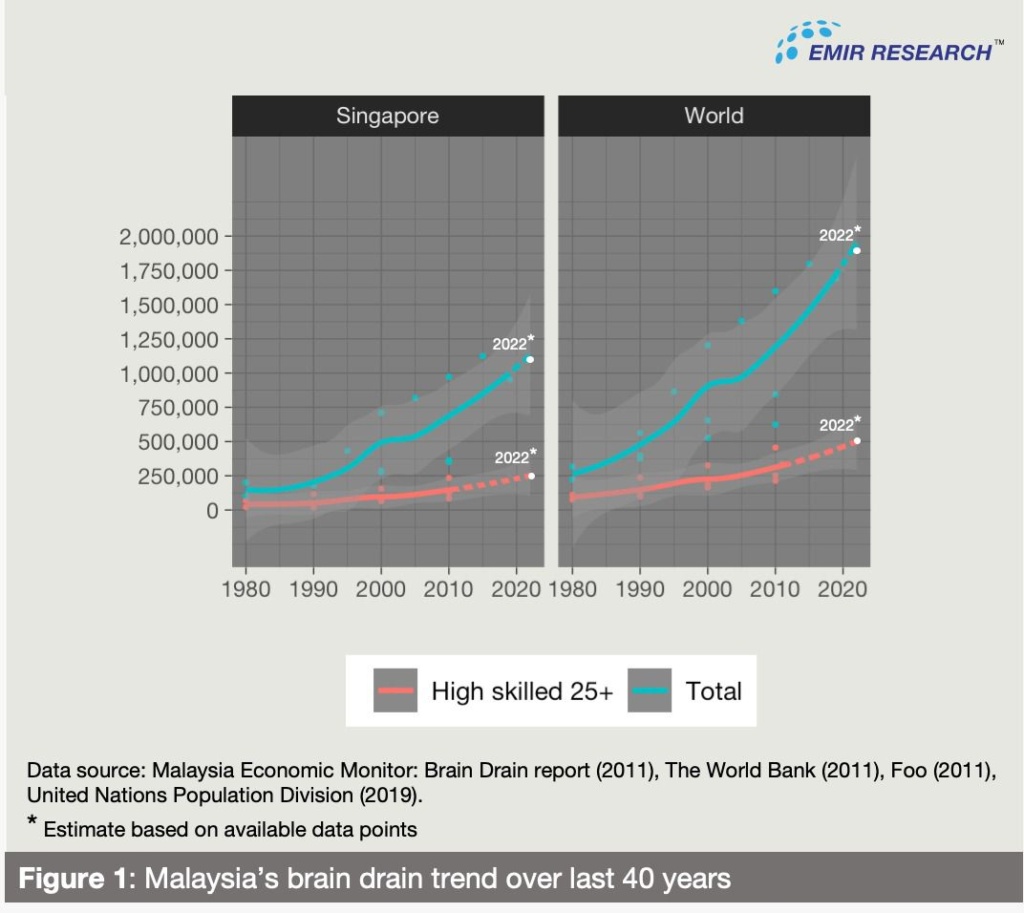

Of course, not many studied about the brain drain at that time nor was there important data collected. However, the earlier estimates we see reported shows us that in 1980 there were already between 76,000 to 110,000 highly skilled Malaysian diaspora, aged 25 years old and above, living in other countries (60% of these lived in Singapore).

Large numbers for a country of 13.8 million at that time? Large.

In 2000, the researchers estimated that for highly-skilled migration rates, the world average rate of brain drain was about 5 per cent, while for Malaysia it was 10 per cent in that same period. At that time, it was still less acute than in other regional economies such as Singapore (14.5 per cent) and Hong Kong (29.6 per cent). However, we see where these economies are now. Singapore’s Human Flight and Brain Drain Index has been in steep decline, especially since 2014 and by now, Singapore is at the very bottom of this brain drain rating list (160th place out of 173 countries). This country has realized what essential resource it needs to ride the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) wave.

On the contrary, as EMIR Research has recently reported in “Malaysian brain drain – don’t go chasing waterfalls”, the Malaysian brain drain has been growing exponentially over the last 40 decades and by now accounts for around half a million highly skilled individuals dispersed around the world (Figure 1).

The total stock of Malaysia’s diaspora is estimated to be slightly over 2 million. However, out of this number, only half a million constitute highly-skilled individuals above 25 years old who are more likely to be employed in various professional fields, even though these numbers are still imperfect estimates subject to various challenges.

With regards to the specific type of profession breakdown, there is an absolute void of granular data. However, from the media reports and existing empirical work in the Malaysian context, we read much about Malaysian highly trained medics and accountants being in demand abroad.

Given the weak 4IR eco-system in Malaysia, it is logical to expect, a very limited number of bright individuals with a high level of technical and ICT-related skills that Malaysia was able to breed, also choose to find application to their abilities abroad — they have no choice.

The scope of professions that Malaysia can supply to the world is naturally limited by the human capital base as the end product of domestic education. And we know that our education system has been weak and inadequate to the needs of 4IR for some time.

Already in 2009, World Bank, based on its surveys, reported a serious shortage of high technical skills in Malaysia, including among fresh grads, therefore, reflecting serious problems within the education system. This dynamic continued well into 2015 and till now.

TalentCorp reported digital-related occupation skill mismatch since 2015/2016. As adduced from their Critical Occupation List, occupations requiring high skills and knowledge related to ICT, electronics, engineering, and research have been consistently listed as “hard to fill” since 2015 until now. Noteworthy, as revealed in the details of the same yearly report by TalentCorp, these vacancies are difficult to fill even when the employers offer higher salaries to attract critical talents. Also, as some employers disclose, there is steep competition for these critical occupations from abroad.

At the same time, our youth unemployment is at its historical high.

One more fact is already in 2010 World Bank survey found that a large share of diaspora acquired education overseas.

So what does this all tell you?

The direly needed high across all the industries technical skills, even if acquired in Malaysia, are not filling the existing vacancies but are highly likely to be employed to advance foreign economies.

Even if the domestic stock of tertiary-educated continues to be replenished quickly enough compared to the outflows measured by the numbers, our education system is not producing the talents in the required numbers. And even those hot hunted talents are likely to seek better opportunities abroad and not so much because of higher salaries and better perks, but overall innovation-oriented culture and thriving digital ecosystem.

Given the global demand for 4IR related skills, we might expect these talents to be abundant in Malaysia`s latest migration stock.

What is the root cause for this alarming trend?

The accumulated empirical evidence (quantitative and qualitative) on brain drain, specifically in the Malaysian context, from 2009 to 2020 offers quite a multi-dimensional explanation of the brain drain phenomenon.

The “push” factors originally come from the home country (Malaysia in this case) and consist of elements that motivate people to leave the country. Here we find factors like unjust policies and social injustice (ethnicity-based rather than need and merit-based); the limited breadth and depth of the job market, job-related stress and dissatisfaction; extreme conservatism, bureaucracy, hierarchy and rigidity in social, political and institutional settings versus dynamism, creativity, autonomy and innovation; lack of intellectual stimulation; low quality of education; low quality of life, i.e., cost of living, poor work-life balance, security issues, corruption etc.; political and, as a result, economic instability, scepticism over country’s prospects (this item consistently surfaced in empirical findings since 2010); ethic polarisation, segregation and tension at every level in society, i.e., institutions, family units etc.; weak institutions; subjective norm pressure from important others such as family, friends or colleagues.

On the other hand, the “pull” factors attract Malaysians abroad. Here we see equal opportunity; better career prospects in terms of promotion as well as breadth and depth of the job market; better perks, i.e., salaries, benefits etc.; better opportunity to acquire new skills and knowledge; the personal goal for advancement and development; the high quality of education; higher quality of life, i.e., better standards of living, secure environment etc.; social and economic stability; ability to adapt to the culture.

However, if we look at it carefully, the core underlying problem behind all of these factors is poor governance, poor policy planning and/or execution: biased, corrupted, populistic, suboptimal, identity-based, divisive, haphazard, unfair, inconsistent, complacent, incompetent, regressive and simply outdated.

Yes, ironically enough, the high quality of country stewardship requires high skills too.

Until this changes, we will not be able to reverse our brain drain.

This is not an appeal to the policymakers at all. The policymakers have already demonstrated their disinterest in the brain drain phenomenon and other destructive processes.

This is a real wake-up call to all the Malaysians. Such an attitude as “let them leave” will not take us all as a nation too far anymore. The situation is critical. The dynamics that are taking us all into a drain, together with the brain drain, among other things, and the root causes are very clear—we need a high-quality country’s stewardship. We need to remember this in GE15.

The current situation is very critical, but the worst is probably just an inch away.

The global empirical research links the persistent brain drain issue with various structural problems for its home country, such as ageing population, low intellectual and academic standards, starvation of talent replacement, low aggregate creative potential, poor governance and policymaking, middle-income trap, low industry development (less breadth and depth), poor quality of life, poor economy, low foreign direct investment, fewer job opportunities and corruption. What does not Malaysia have out of this list by now?

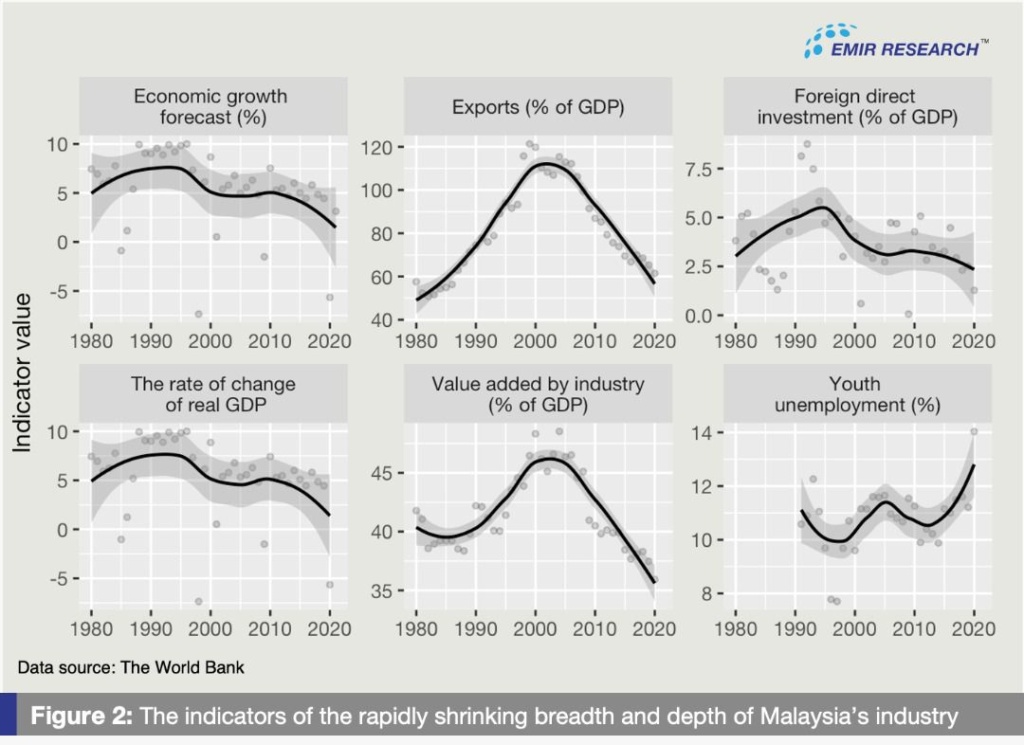

We should be really worried about our low industry development as it is at the root of many other destructive processes in the country, including exacerbated inflation. It is not just the excessive money supply that feeds the inflation. It is low industry development that sends the country into a real tailspin fall. Sri Lanka is the perfect example of it.

And here in Malaysia, we observe the carbon copy of the Sri Lanka scenario—the decades of addiction to subsidies and government handouts as bad substitutes for the credible management and crisis preparedness policies. This led to a gradual loss of competitiveness, innovativeness and productivity, turning Malaysia into a nation of consumers versus producers, specifically in value-added products and services.

And the ballooning national debt, even though not external, represents a considerable opportunity cost for the nation, leaving it with little space for productive use of the scarce revenues.

If we look at Malaysia’s numbers reported by the World Bank for such indicators as economic growth forecast, exports as per cent of GDP, foreign direct investment as per cent of GDP, the rate of real GDP growth or value-added by the industry as per cent of GDP, they all are in steep decline since the 1990s – 2000s (Figure 2). At the same time, our youth unemployment is on the steep rise since the same period. These are clear signs of the domestic industry being in serious trouble.

In other words, we are full steam heading into Sri Lankan scenario if we do not address the main problem—the quality of the country’s stewardship. Brain drain is only a symptom.

Dr Rais Hussin is the CEO of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

[ad_2]

Source link