Published by AstroAwani, SinarDAILY & theSun, image by AstroAwani.

As Malaysia heads towards being an aged nation, effective policies are needed to prepare for and mitigate the drastic impacts of this inevitable phenomenon. They should be strategic and well-implemented.

Ageing population is a phenomenon where older individuals become a larger share of the total population.

According to the United Nations (UN), an older person is defined as a person aged 60 years or over, while, globally, many countries, including Malaysia, define ‘elderly’ as a person aged 65 and above.

UN studies indicate that the global population aged 65 and over is growing faster than all other age groups. The organisation also estimates the population of individuals aged 65 or older surged from approximately 260 million in 1980 to 761 million by 2021. Furthermore, from 2021 to 2050, the worldwide proportion of older individuals is anticipated to rise from under 10% to approximately 17%.

World Health Organisation (WHO) observes a similar trend in its reports and believes it will gain even more momentum in the coming years, especially in developing nations, including Malaysia.

According to the most recent estimates by DOSM, the composition of the population aged 65 years and over (old age) increased from 7.2% in 2022 to 7.4% in 2023, encompassing 2.5 million people, indicating that Malaysia is experiencing population ageing.

DOSM also projects that Malaysia will have a nearly equal share of the young (18.6%) and older population (14.5%) in 2040. The old age group will surpass 6.0 million, transitioning Malaysia into an aged society.

Several factors contribute to this shift in population dynamics, with changing fertility rates, life expectancy, international migration and industry structure playing crucial roles.

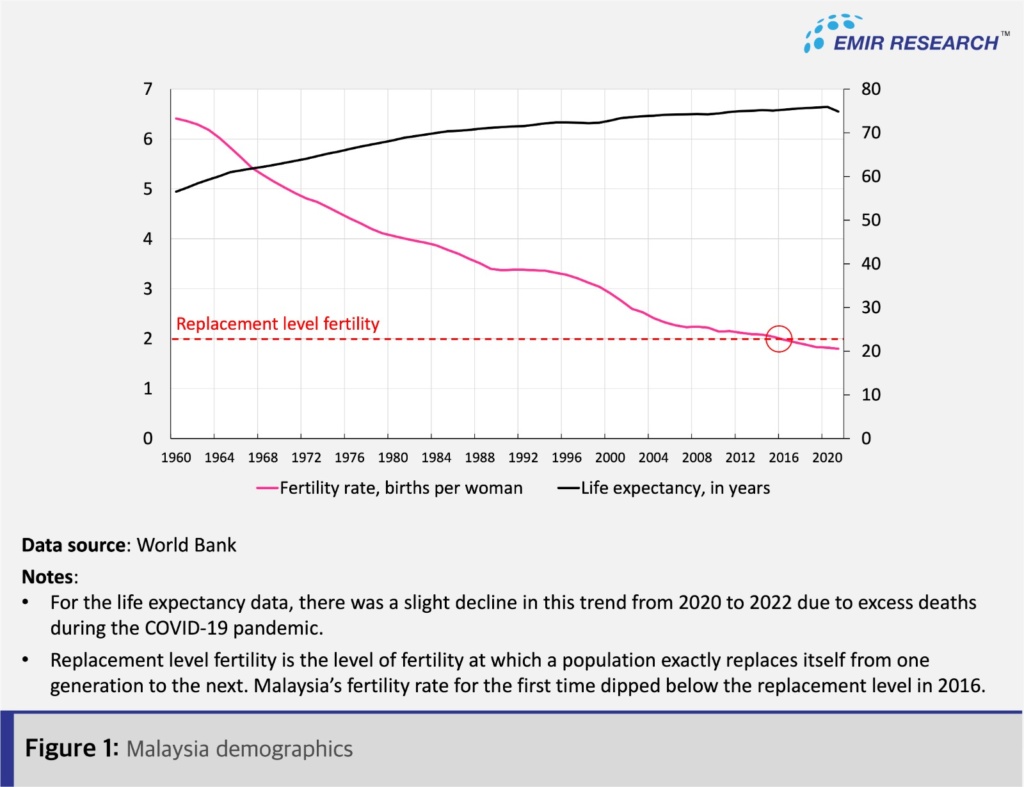

For instance, in Malaysia, a substantial decline in the fertility rate has been observed in recent years. According to the data from the World Bank, the latest reported data on the fertility rate for Malaysia in 2021 is 1.8 births per woman – a substantial decrease from 6.4 births per woman in 1960, accompanied by a steady increase in life expectancy among Malaysians (Figure 1).

According to DOSM, the composition of the population aged 0-14 years (young age) in 2023 decreased to 22.6 per cent compared to 23.2 in 2022. The decline in fertility rate continues despite the efforts made by the federal government to assist working women, such as the 2020 federal budget, which includes various measures and incentives to support working mothers – i.e., a two-year RM500 monthly incentive for women aged 30 to 50 who re-enter the workforce and an extension of maternity leave from 60 to 90 days.

Hence, the government must re-evaluate the initiatives using the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework for impactful policies that EMIR Research has strongly advocated in numerous articles.

To address declining fertility rates and promote higher female workforce participation, the government must collaborate with the corporate sector to enhance on-premises childcare facilities and implement flexible work structures catering to working women’s needs. Mobilising all under-utilised talents in the economy (female workforce, unemployed, underemployed, retired) to realise their full productive potential is paramount to mitigating the impacts of an ageing society.

In countries that are experiencing large immigration flows, international migration can slow the ageing process, at least temporarily, since migrants tend to be in young (working) age groups (Peri, 2020). Therefore, a significant brain drain from Malaysia could also contribute to the ageing population as it represents the outflow of younger people to study or work and permanently settle down abroad, causing a lower proportion of working-age individuals in the home country.

In the World Bank’s Economic Monitor (2011), “social injustice” ranked as the second most significant migration driver at 60 per cent, following “career prospects” at 66 per cent, unambiguously suggesting the critical focus areas for impactful strategies aimed at returning bright individuals. It is better to start putting such plans forward as many experts foresee that by analogy with global “currency” and “trade” wars, “migration wars” for the highly skilled younger ones will become a new reality very soon.

The impact of an ageing workforce on the economy also depends on the structure of the economy itself. The higher the share of physical, semi-skilled jobs, the more difficult it is to combat the effects of ageing. As an ageing population, Malaysia can no longer postpone taking measures towards a massive shift from low-productivity low-skilled sectors to high-productivity high-skilled ones to avoid fiscal catastrophe in the not-so-distant future.

To maintain GDP growth, it is necessary to develop capital-intensive, knowledge-intensive, and technology-intensive sectors (massive digitalisation and digital transformation) since due to the ageing population, the contribution of labour to the production function will continue to decrease. This kind of industry transformation shall also slow the brain drain, among other positive national impacts.

In the absence of proactive measures, population ageing can profoundly impact Malaysian society.

Among the serious consequences of a reduction in the working-age population is a decrease in labour productivity and total savings, and therefore a slowdown in investment, demand, and economic growth with increased fiscal and political pressures concerning public healthcare, pension, and social protection systems.

Also, a falling fertility rate in an actively ageing economy reduces the effectiveness of monetary policy since the aggregate demand of the older cohort is less sensitive to changes in the interest rate, as per International Monetary Fund findings. At the same time, a lower birth rate in the long term reduces supply in the labour market, which leads to a fall in supply in the goods market. However, an increase in the share of net consumers (pensioners) with a decrease in the share of net savers (young people) causes excess demand in the goods market, which, in turn, may accelerate inflation.

With retirees outnumbering the working-age population, there’s a risk of declining tax revenues, potentially causing pension payouts to outstrip contributions from younger workers. This could significantly burden the younger generation, raising concerns about inter-generational equity.

Policies must be thoughtfully crafted and implemented to counterbalance the ageing trend and mitigate the adverse effects of this demographic change by establishing an efficient ecosystem for the elderly to strive and sustain their livelihood and living.

Much attention is needed in health and social care, transportation, urban planning, income security and employment.

To tackle challenges from an ageing population, Malaysia could consider automatic adjustment of retirement age with increasing life expectancy (this mechanism has been implemented in Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Finland).

Malaysia could consider the World Bank’s suggestion of a gradual increase in the retirement age from 60 to 65 over ten years, allowing the public sufficient time to adapt to the changes.

According to the Economic and Monetary Review 2022 report by BNM, it was stated that one of the urgent policy gaps is the issue of insufficient savings for post-retirement life.

The retirement age in Malaysia currently stands at 60 years old, while the minimum age for EPF savings withdrawal is 55 years old. To discourage early retirement, the government could consider amending EPF regulations to allow fund withdrawals only at the age of 60 or older, with exceptions considered for exceptional cases subject to individual assessments.

Furthermore, retirees should have withdrawal limits to prevent lump sum withdrawals. Allowing such withdrawals has led to many elderly Malaysians, often early retirees at 55, spending their entire EPF savings within a few years.

According to Holzmann (2014), most retirees use up their EPF savings within five years.

Per the report published by DOSM on 28 September 2022, Malaysia’s life expectancy in 2022 is 73.4 years. This means that the government needs to place regulations to ensure retirees’ EPF savings last them throughout their retirement.

Another policy option for the government is to promote the immigration of highly skilled young individuals through less restrictive VISA policies. The government should also aim to incentivise existing immigrants by allowing longer VISA durations for those who demonstrate good conduct in their workplace and establish themselves as valuable contributors to the Malaysian economy. The government also should target bright and talented international students encouraging them to stay and work, especially in the critical void occupations (See, “Malaysia needs more highly skilled workers for competitive edge”).

A larger proportion of working-age immigrants can also reduce the age dependency ratio, which was 43.22% in Malaysia in 2022.

Healthcare costs are another expense to consider because retirees are more susceptible to illness.

Since a portion of the income must be set aside in the EPF for retirement purposes, a similar system could be introduced to cover healthcare expenses during retirement. The government could allocate a small portion of EPF contributions to create a dedicated fund covering post-retirement healthcare expenses.

For example, Singapore practises a similar system, where employees contribute to their Central Provident Fund (CPF), under which they have a Medisave Account, specifically designed to cover healthcare expenses – Ministry of Health, Singapore.

Currently, many retirees rely on government budget subsidies for healthcare expenses. With Malaysia’s ageing population, this strain on the budget is expected to worsen.

Although diverting some EPF funds to a healthcare account reduces retirement savings initially, it’s important to recognise that a significant portion of these savings is typically allocated to post-retirement healthcare expenses, offering long-term financial benefits to retirees.

Post-retirement employment plays a crucial role as the population shifts into an aged society, offering economic benefits from multiple angles. To facilitate this, creating old-age-friendly workplaces for elderly individuals seeking to rejoin the workforce is essential. Government initiatives, such as income tax reductions to employers hiring older workers, can encourage active participation in the labour market.

This is highly linked with inclusive urban planning, which involves the integration of elderly-friendly amenities to facilitate easy commutation of the elderly and improved mobility.

Retirees’ participation in the labour force can enhance overall workforce numbers, thereby increasing economic productivity. This aligns with the Madani economy framework’s goal of raising the labour share of income to 45% of the total income.

Increased senior workforce participation can boost domestic consumption, creating a win-win situation for both the ageing population and the broader economy.

The decline in family support for the elderly, driven by smaller families and increased female participation in the labour force, has impacted the well-being of older individuals.

It’s crucial to explore alternative care options like elderly care centres and retirement villages equipped with readily accessible medical services. For instance, these retirement communities could include government-funded clinics offering free primary healthcare.

While the ageing population presents challenges, it also offers numerous opportunities. With the right strategies in place, ageing populations can become valuable contributors to society and an additional stimulus for economic growth. Dr Rais Hussin and Chan Myae San are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.